Biochar can prevent PFAS from leaching into the environment

New research shows that biochar made from sewage sludge can slow the spread of PFAS from contaminated soil. Field trials and modeling suggest that most of the soil contamination can be held back in the soil for up to one hundred years.

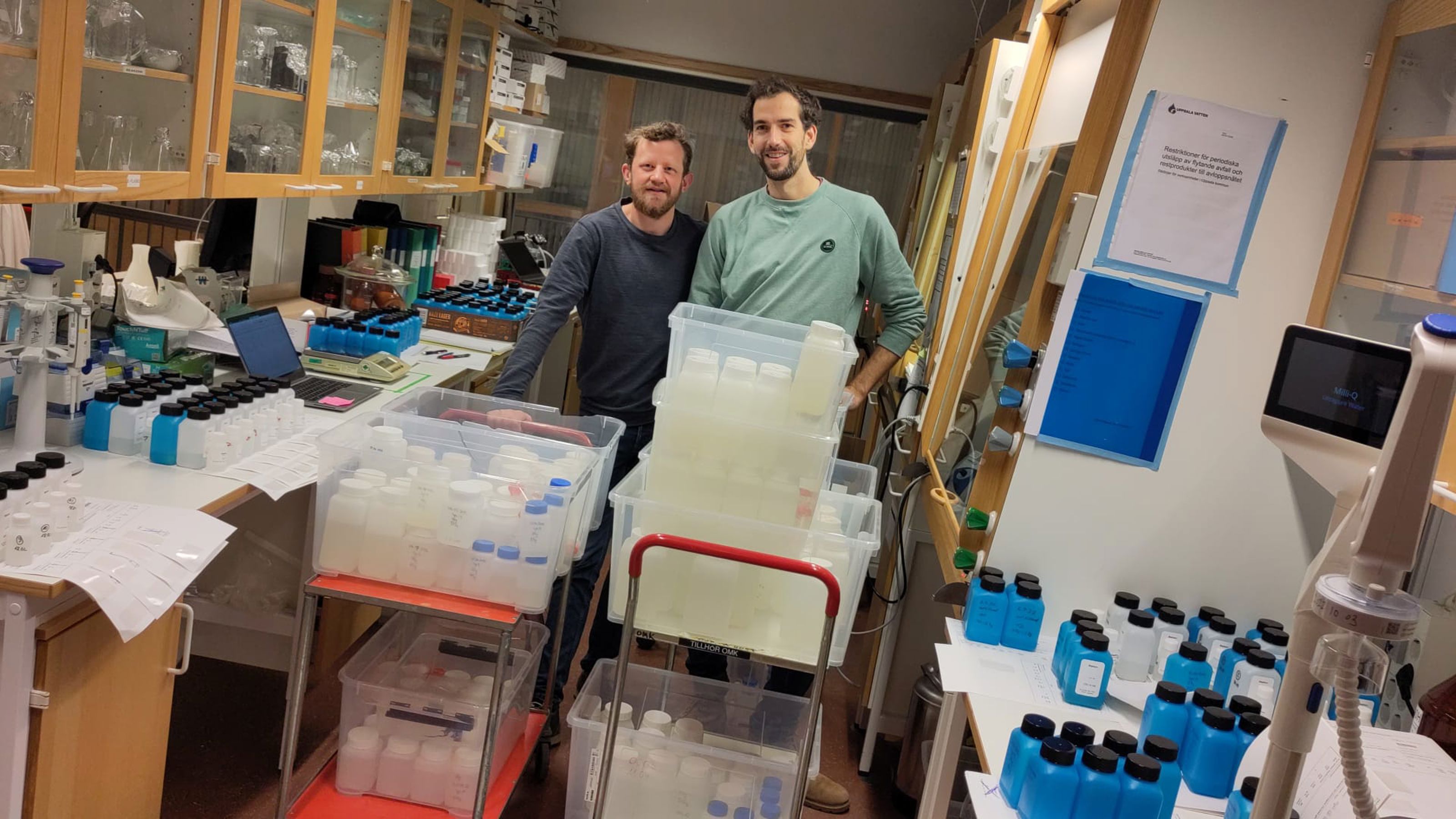

Michel Hubert from NGI (to the right) and Björn Bonnet from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) analyze soil and water samples for PFAS in the laboratory. The researchers collaborated in an EU-funded project where biochar was tested in the field over the course of one year. ( NGI)

A European doctoral research training program, PERFORCE3, has provided new knowledge about containing the environmentally harmful chemicals PFAS.

"PFAS are extremely stable molecules; they spread easily in nature, are toxic, and can cause serious health effects", says Hubert, a Senior Engineer in NGI's Department of Environmental Geotechnics.

Hubert came to Norway from Germany five years ago to join the EU-funded PERFORCE3 Innovative Training Network, which is funded under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions. The project, coordinated by Stockholm University, included fifteen PhD students across Europe. NGI participated as a partner and hosted Hubert’s research. His PhD was awarded through NTNU, where he recently defended his thesis under the supervision of Prof. Hans Peter Arp, who is affiliated with NGI and NTNU.

An invisible environmental threat

Since the 1950s, PFAS have been used in everything from firefighting foam and food packaging to rain jackets. They make surfaces water—and grease-repellent, but at a cost: they do not degrade, they accumulate in nature, and they are now found in blood samples of humans and animals worldwide.

"I often say that global PFAS pollution is just as serious as plastic pollution, which was recently focused in the media due to a possible global plastic treaty. The difference is that we cannot see them. When environmental problems are invisible, they are easy to ignore", Hubert says.

Surveys show thousands of contaminated sites across Europe, many linked to airports and firefighting training facilities. In Norway, for example, Oslo Airport stands out as one of the areas with high PFAS concentrations in soil.

The EU has spent many years restricting the use of only a couple of the most hazardous PFAS compounds, out of a family of more than 10,000. In the meantime, the industry has developed many new variants.

"The result is that policy lags behind reality, the regulations cannot keep up with chemical development", he says.

Michel Hubert recently completed a PhD on PFAS contamination at NTNU, focusing on how biochar can slow the spread of the so-called “forever chemicals.” ( NGI)

From research to practice

Hubert stresses that neither method can "wash the world clean." They must be applied strategically where contamination is most severe and in so-called treatment trains where different remediation techniques complement each other to achieve high efficacy

"It is about hotspots – areas where contamination is so concentrated that it threatens drinking water and ecosystems. Airports, industrial sites, old paper mills. That is where we must act. Otherwise, these chemicals will keep spreading", he says.

At the same time, he points out that cleanup is only the final step.

"Cleaning up PFAS contamination is expensive and demanding. The most important thing is to prevent emissions and reduce use. The EU is now discussing an 'essential use' concept, where PFAS would only be allowed in truly necessary areas, such as medical equipment. That is the way forward", says Hubert, who is now involved in new EU projects and consulting work for industry sites with PFAS problems.

"It is rewarding for me to work with applied research. Using knowledge directly in projects that help address the PFAS problem means a lot. We cannot solve it alone, but we can help prevent the situation from worsening", Hubert concludes.